Kodak 1882. “One of three in the world.” http://instagr.am/p/gza14/ Kodak 1882. “One of three in the world.”

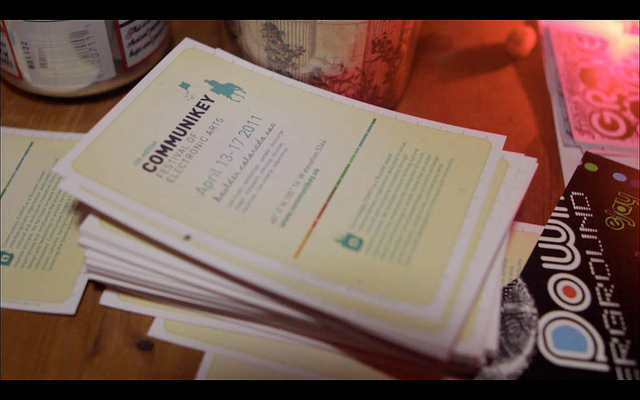

For those of you who do not know I am in the midst of my biggest project to date, a short film- documentary on the Communikey music festival and organization (check it out @ www.communikey.us). It has been an incredible learning experience thus far and have had a great amount of support up to this point. I will continue to post and update about the project as I go along.

I feel like this is an extremely important story to tell, not only because many of these people are my friends and an incredible talented group of diverse creatives but because this group of people continue to inspire me and others to participate in the active creation of a new and better world. This organization’s passion for the intersection of music, technology, sustainability, design and cultural exchange of ideas is fueled by their love of participating in the creative process. It is in the skillful means they use to achieve the opening of these new interstitial spaces, where together, those fortunate enough to co-create this experience can explore living in and practicing life outside the socially constructed boundaries of what can and cannot be done.

(by Scott Kaplan)

An Article that will be published in The Sycamore (full version)

This is an article I wrote for Naropa’s Sycamore (our new student run newspaper) in its entirety, as it will be run with a significant amount edited out due to print space restrictions. FYI this article covers my experience in breath not depth here. I will continue to go more in depth in my experience as the coming weeks unfold…

I’ve got to be honest, I’m much more comfortable letting the camera do the talking from a journalistic standpoint, especially coming the from the still very raw and undigested state I’m finding myself in. However, with that being said, I’ll just start out saying the phrase “hit the ground running” doesn’t even come close to the whirlwind experience of arriving in Nicaragua. Our first two days in the capital city of Managua consisted of going to clinics and shelters (one where we actually helped serve lunch), a landfill community called La Chureca, the conducting of neighborhood door to door visits, a stop at the first fair trade shop (apparently in the world), and a trip to a village (consisting of primarily relocated residents of La Chureca) where we played games with children. At every location we visited we were thrown into conducting interviews with nearly everyone we encountered; once even rushing to catch up with sweatshop workers as they left the factory between shifts. Awkward and difficult at first, we soon grew into the reoccurring habit. In Managua we also visited a university, an elementary school and shuttled back and fourth to the airport many times to hunt down a few lost bags and some delayed students… The next ten days were spent far in the north of the country in the Jalapa Valley, about 20 kilometers from the boarder of Honduras where we lived with host families as we worked along side PIEAT and members of the local community of La Tierra Promitera- “The Promised Land”.

Once in Jalapa, we participated in the construction of a school for children as well as planted gardens and explored sharing some contemplative practices (such as yoga and other relaxation techniques) with the locals as well as continuing to conduct more one on one interviews. Mostly with the help and guidance of our wonderful translators, many of who were members of PIEAT.

Local residents of La Tierra Promitera (“The Promised Land”), during a house visit the mother voiced concerns for her infant daughter’s health because of an apparent diagnosed heart condition. She hopes PIEAT can help her find more support or resources for healthcare.

Local residents of La Tierra Promitera (“The Promised Land”), during a house visit the mother voiced concerns for her infant daughter’s health because of an apparent diagnosed heart condition. She hopes PIEAT can help her find more support or resources for healthcare.

We got a chance to visit local tobacco barns and the factories where cigars were made, where a significant population of Jalapa works in these, or similar conditions.

Possibly the son of a tobacco barn worker or could very well be one himself. A whole days work consists of stringing together pesticide covered tobacco leaves for what equals roughly $4 US.

Possibly the son of a tobacco barn worker or could very well be one himself. A whole days work consists of stringing together pesticide covered tobacco leaves for what equals roughly $4 US.

Exposure to such conditions was an important and yet similarly frightening thing to see, much like an experience of a tour we got inside a local hospital too.

The Mothers often do not breast-feed infants because it is seen as a privilege in their culture to be able to afford the infant formula, and because of this infants often suffer various health consequences like this infant seen here. Note : a bottle of milk on the counter.

The Mothers often do not breast-feed infants because it is seen as a privilege in their culture to be able to afford the infant formula, and because of this infants often suffer various health consequences like this infant seen here. Note : a bottle of milk on the counter.

Only one day was spent away from our work in Jalapa, when we got a chance to spend a night up in a remote mountain village and then make the (sweaty) five-hour hike down the following day. Having such a diverse exposure to so many different people, and situations was no doubt amazing and life changing for us all.

My personal reasons for going down to Nicaragua were really based in a desire to put theory into practice. To confront my own assumptions and ideas of what poverty was, while expanding my knowledge of such things both conceptually and contextually.

Unlike any other travel experience, I had to immerse myself in the culture and foster a reciprocal relationship with the people on the land. Empowered by a demand for hands on participatory action research, I found it necessary to delve deeply into the stories of people’s lives and their personal experiences. It became so important to ask hard questions and listening deeply. I found myself face to face with the realities of poverty, ecological destruction, socio-economic and gender discrimination existing in a more contrasted, real and concrete way for me than ever before. In the past it might have been easy for me to ignore or have been blind to such issues in the abstract context of the classroom, or in the context of life in Boulder (just because it is so familiar by now), but here these things visceral grabbed my attention and wouldn’t let go.

When I had my hands in the earth, planting fruit trees along side the mothers and daughters, husbands, sons and brothers of La Tierra Promitera (“The Promised Land”); feeling the sweat, seeing the smiles, playing with the children, conversing as best I could… this interaction and sharing of space, time and story, added an extraordinary new dimension and level of meaning to the work.

Community members receiving the fruit trees that will be planted in each households yard.

Community members receiving the fruit trees that will be planted in each households yard.

The connections nurtured through dialogue and storytelling all had the backdrop of working on projects with a common purpose, this caused a real inner shift to occur. Something had begun to unravel, for all of us on the trip I think, through the process. It became possible through such work to observe truths that had been missing or obscured from our collective picture of reality. Most of what I have taken away was found in the practicing of this kind of relationship. There was an attempt by all of us, I feel, to breathe into the diverse concrete experiences of living and working along side the people and the land of Nicaragua as best we could.

A great deal about life and poverty in Nicaragua was learned from the family I lived with and those who’s homes and workplaces we regularly visited; mostly through witnessing and participating in the routine of what was their daily life or through the co-creative activities like planting garden beds.

My host family cooking dinner. The mother Alba, Grandmother (forgetting her name) and nephew Elwin, along with their dog Blinky.

My host family cooking dinner. The mother Alba, Grandmother (forgetting her name) and nephew Elwin, along with their dog Blinky.

The lessons were found somewhere in the morning bus rides interacting with the locals, in the sound of my host mother’s voice who tells me quietly, that she must spend 8 months out of the year away from her children working in Costa Rica as a nanny. It was somewhere in the joy of seeing the children smile while learning to play a new game- allowing them to be children again and to forget about the demand of tending to their own siblings.

Children of El Tismal playing under a parachute.

Children of El Tismal playing under a parachute.

It was in the handshakes and words of thanks after a house visit or stones were hauled and concrete was mixed and poured. It was there on the faces of those who worked in the fields and in the factories.

Teens hanging tobacco leaves to dry in the barn.

Teens hanging tobacco leaves to dry in the barn.

Woman taking her lunch break, working in the tobacco rolling factory.

Woman taking her lunch break, working in the tobacco rolling factory.

It was in simply showing up every day in the community, being present and showing our care by giving the most of what we could, even if it was only to listen and hear their story.

The beginning of an environmental disaster. Relocated residents of La Chureca, who now live in El Tismal have requested garbage be brought to their new location because scavenging for waste such as scrap metal or electronics is currently seen as the only means of employment.

The beginning of an environmental disaster. Relocated residents of La Chureca, who now live in El Tismal have requested garbage be brought to their new location because scavenging for waste such as scrap metal or electronics is currently seen as the only means of employment.

By no means was this trip all about helping people who are helpless, because from what I’ve seen, those people don’t exist. It wasn’t about any one group of people coming to save another, it was about finding some truth through working in mutual responsibility, and that’s something I’ve really awakened to. It’s a humbling experience and a kind of magic that happens when people regardless of background come together united by a desire to change the status quo. I feel we all become liberated just a little bit more when we work in solidarity. This is not to say that things become easier, often times far from it. But this experience has remind me that real change doesn’t come from sweeping legislation or powerful sounding edicts, but in the experience of sharing knowledge and wisdom organically through a heart to heart connection. The experience has showed me just how much time and patients this really takes, and it has also made me believe more so than ever the quote by Gill Scott-Heron which reads ‘Nobody can do everything, but everybody can do something’.

Sifting Through The Memory Banks pt.2...

Day 2…

3/15/10

We started early in the morning leaving the hostel and loading up the bus with all of our bags, after a hearty breakfast of rice and bean and scrambled eggs.

We headed first to what was apparently the very first fair trade co-op in the world. From the looks of the place I would have imagined it to have been simply another sweat shop, but once we interviewed one of the women as she worked, she told us that at the sweatshop she had in fact worked at previously before working there, that they were treated much more poorly, that they could be fired without any reason given whatsoever.

For five days a week for probably 8-10 hrs, her job is to sew the tags onto the back of the shirts, this is the only task she does. I am still hesitate to call this “fair trade”… Although more of the proceeds go back into the pockets of the women who work here than would those at a corporate sweatshop.

From the fair trade clothes company we headed to what was supposed to be a ceramics shop but it turned out that it was closed, so we ended up traveling to a Barrio where Debbie had established contacts with some of the local residents and had arranged for us to visit and talk with them. The neighborhood was my first face to face encounters with the extreme poverty of Managua. We spent almost an hour making house visits with some of the locals, it was extremely awkward at first. Simply meandering up to a strangers home with our translator Jorge (who as I will talk about more latter ends up becoming a fantastic friend) and trying to ask questions about their life with little or no provocation. At first it felt very intrusive simply walking in and asking people about their life, which to them I’m sure seemed perfectly normal, but from the appearance of a bunch of wide eyed gringo’s I’m sure it appeared as if most of us though that they’re living in real poverty (But what I knew better was that even these people were far better off then others I would come to meet).

The first family I visited the boy Obando came to the door first and then his mother Nelly and his father Eddy came out and greeted us and invited us in. Me and Corey went into the house into what was set up like a living room which was probably about a 5 x 7 where we sat and asked them questions about their work, their worries and the members of their family including their children. The father makes cookware at a factory during the day and the mother stays at home and takes care of the two boys. They worry about loans they have taken from the bank and if they will be able to pay them off.

The next family we visited was a few blocks walk from the first house, the woman who took us was living with her entire extended family, which was her husband and around 8 others children. He is the sole breadwinner acting as a school security guard, he plays the guitar and so does one of his sons, they were about to play a song for us but it was time to leave, like most of the places we visited things always felt too rushed. It was painful at times leaving these people so soon after just getting a glimpse into their life, it actually felt to me disrespectful to simply run into a neighborhood, ask questions and leave in a hurry to another location. Like taking something without giving too, it’s simply never sat right with me…

After the barrio we left and went to a market to buy food for a rushed and chaotic lunch on the moving bus. Bouncing about trying to hurriedly eat piping hot tortillas stuffed with cut up avocados, cucumbers and tomatoes can be quite a messy experience… At the market there was a group of women gathered singing out of a PA system some evangelical gospels.

While I was searching for some oranges, I ran into a group of older men who had obviously been high or drinking early in the day, one of the men who looked african american (which I found interesting because I probably saw less than a I could count on a hand the whole time I was there) spoke very good english and asked me about where I was from, we talked for maybe five minutes he told me about the states, which made me think he was not a native too. The group was calling me so I told him I had to go, he said how nice it was to meet me and I thanked him too and jumped on the bus, I can’t for the life of me remember his name now…

We went to the airport looking for the missing donation bags as well as Bree and Loreal which still hadn’t arrived. No luck.

So after lunch we went to the University of Nicaragua. We visited two classrooms, talke to students learning english and then lift again in a scramble as we were trying to catch the sweatshop workers as they were leaving the factory. Between 4 and 5 o’clock is when the shift change occurs.

People come pouring out of the factory. I expected to see lots of children or people who looked disheveled but supsisingly people were well dressed and looked as if they were ready to go out for the night with some exceptions of course. Like this woman who was scrounging for change outside the entrance, the security guards didn’t like me taking pictures either…

We spent the next two hours there interviewing person after person about their lives, their jobs and their feelings surrounding the sweatshop institution. It was incredible to hear their perspectives, each bringing a different reason, idea or concern for why they found themselves working there. It was also very common to hear some of the same scripted answers to questions about how long their shift was, how they were treated etc.

One of the things I had to get use to over the course of the trip was listening for these scripted responses by workers. One has to understand not only the circumstances under which the questions are being asked but also the historical context of much of the countries history in order to fully understand why people cannot answer as truthfully when posed questions.

Its very common for people to lie about things because of the incredible amount of fear which is used to control them, they are told to not talk to anyone and that if they do the company will fire everyone and will take their business out of nicaragua to another country and everyone, not just them,will be out of a job. So most people choose to stay silent. Nicaragua has been a victim of a culture of silence for the better part of its history, or atleast since western eurocentric interestests have shown interest in the regions labor and resources. From the contra wars , to the oppressive dictatorships and revolutions that have taken place inside and across its boarders(that we have helped fund and train most of the militant forces right in good old Georgia at The School of Americas. Look it up.) it has been deeply wounded. Both it’s land and people.

A culture of silence can never heal, because it can never name the object of its oppression and therefore cannot retain any power; it is consumed by fear and terror and unable to seize authority or rightful ownership over itself. Here in america we might think something like this preposterous, that it couldn’t exist here but even in america there are places where this is true, there are companies many of whos products we probably use on a regular basis, whos employes (mostly immigrants) are put into similar circumstances… what affect does this have on you and me? are we part of a system that produces cultures of silence? How do we not know things like this exist, is it because we ourselves function within our own culture of silence?

Finally after our very long day we made it back to the hostel exhausted, sweaty and grateful for food and a bed.

Sifting Through The Memory Banks pt.1...

Day 1 of Total Recall…

3/14/10

Arrival.

Spent the first 45 minutes in Customs talking with a native who was living in LA, we talked about some of the spots I had been to during the weeklong trip I had taken back in January. Turns out the guy is a pharmacist, so we joked that if I got sick here in Managua I’d know someone who has the good drugs to take care of me.

We finally grabbed our bags and loaded up the school bus type van, where we were helped by two children, very disheveled looking; one who was either high on drugs or deaf because he was not very responsive to instructions even in Spanish. Debbie ran into a college student named Colin, who was on vacation from school (Harvard… ahem..) he was supposed to meet up with a group of other students but none of them made it. So Debbie offered him to join our group and spend the night with us, he was incredibly grateful. Once we were all packed and ready we drove off into the hot muggy Managua night…

The original hostel we were going to be staying at was at capacity so we ended up just down the road. It was really a very nice place, lush with foliage, basic not luxurious but still very nice. We had our own private guest houses, so Gabe, Corey, Colin and I grabbed a house.

Gabe, Corey, Colin and I went for a water run because the water wasn’t safe to drink.

The smells remind me of India, the burning garbage, the clinging sweaty steel and blood mixture that hugs your nostrils…

We walked down the Pan-American Highway for about 10 minutes and winded our way up a few back-roads and found our way to the other hostel named Cairo. We met up with a woman named Elena, who it turns out is a friend of Debbie’s who helps as a liaison of sorts in Managua for some of the programs that Debbie is involved in. She was actually the woman who was arranging us to stay there that night, had there not been 100 college students from Manchester, MA in the house…

She was kind enough to give us a 5 gallon drum of water and a lift back to our hostel in the back of her pickup truck.

I was foolish and decided to leave my camera back at the hostel, neglecting to bring my camera with me I can take advantage of what is really one of the main focuses of my trip, which is learning how to become a better story teller both with and without the camera. Sometimes its very neccary to put the camera away as I have found, because what ends up happening is that I try to fit the world into the viewfinder, instead of opening to the larger experience of the world and everything that is presently happening. Sometimes I hide behind the camera because it takes the force of the emotional impact in a given situation, it may give me the pause to be able to rationalize or step out of my own experience, but this can also be detrimental to the point of covering a story or reporting on an event. How can I be authentically embodied, present and able to tell a story from my own perspective as well as in relationship with the larger experience of those similarly living in the environment and moment and fit these perspectives into the larger picture? No pun intended. How can I without my camera record the images I see with my mind? I can write out the shots I see to inspire me in the future…

Shot:

Corey, Gabe and Colin - Wind in faces, as the dark fuchsia sky encroaches in the background and is shattered by the glare of streaking streetlights.

The Journey has just begun. Tomorrow the work begins.